I was originally introduced to, or maybe a better description would be “baptised by” The Southport Bar with Bruce Harris in the mid seventies. Bruce at the time was the government shark meshing contractor for the Gold Coast. He had been a trawler man, and had owned the trawler Nora but had so much strife in crossing the Southport Bar for his daily shark net inspections that it led to his design of the Shark Cats.

At times when the sea was extremely rough, sand banks would form across the entrance and the only way to get home was to turn his boat Nora beam-on to the seas, and hope that the boat would heel enough on the wave to slide across. Bruce lost two wheelhouses that way!

The Police boat CW Brown, one of the early police boats that we built.

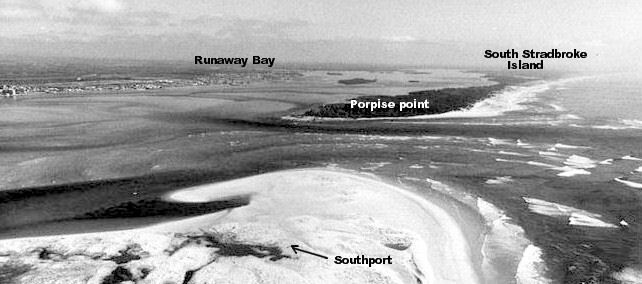

The photo was taken on the old bar entrance around 1978.

I was invited to take a run with him to check his nets in the first GRP Shark Cat. There was a big sea running, and I was not quite prepared for the conditions on the bar that day.

When we reached the entrance we were confronted by a row of breakers.

There was no obvious channel and I was concerned that there was no way to cross. But Bruce was not concerned. He simply headed full throttle at the first breaker. We climbed the wave, smashed through the breaking crest, left the water, and landed in the trough on the other side.

Never before had I been completely airborne in a boat, and even though we landed quite softly on the other side of the break, it was a rather frightening experience that first time.

Up to this time the bar and the broken water had been the downfall of many a boat, and hardly a week went by without a trawler or a yacht getting in to trouble. One of the problems was that the entrance channel moved around with changing wind conditions and it was hard to be sure where the deep water was. Sometimes it meant taking a long leg out to the north-east with the swell coming on the beam. At other times there could be a gutter leading to the south, and at other times there was no apparent opening.

The air trapped between the hulls usually made for a relatively soft landing.

The first recorded wreck in the entrance was the Scottish Prince. Part of her cargo was Scotch whisky. That was in 1887, and even quite recently the odd bottle still surfaces intact, although I haven’t heard of anyone game to sample it. At that time the entrance was about three km south of the present seaway, and had been moving north ever since.

During the late seventies we lived within sight of Porpoise Point and by lining up the corner of our bathroom window and the top of a tree, the line of sight was over the northern edge of the chanel. Within the space of three years that point had moved about fifty meters further north, and during storms we watched tree after tree disappear. Often at night we could see the white parachute flares set off by trawlers as they tried to find a safe passage into the Broadwater, and several times saw the red flares of boats in trouble.

Geronimo

Geronimo crossing before a race.

During the eighties the Southport Yacht Club usually held three overnight races offshore during the year; one being a race to Ballina, and on one occasion after finishing in the early hours of the morning, Air Sea Rescue were waiting outside the entrance to stop boats from attempting to enter the Richmond River. We were forced to wait for three hours before it was safe to go through. On that occasion we planed on the face of the same wave from the start of the breakwater right up into the river itself. Another time after sailing all night in rough conditions we were instructed that the entrance was closed to all boats and our only alternative was to return to Southport. That evening on reaching Southport, and just twenty four hours after starting the race, the Air Sea Rescue Shark Cat was waiting to tell is that the bar was in too dangerous a state to attempt to cross, and it was a case of either waiting till the next morning’s tide to come in, or sail on up to the Moreton Bay shipping channel entrance, and come back through the Broadwater which was another hundred and fifty odd miles.

We decided to sail back and forth all night. It was too rough to even think of trying to anchor. Some of the other boats decided on sailing back to shelter in the lee of Currumbin headland, and one boat tried to enter the Tweed river only to be rolled over on the entrance bar.

Just as it was getting dark Air Sea Rescue came out to tell us that conditions had moderated a little , and if we were willing to risk it, “Cross now.” Of the eight boats waiting outside only two were willing to take the risk.

A big catamaran, and ourselves in Geronimo our RL 34 followed the Air Sea rescue boat to where the channel started. It was beam-on to the seas, and we would have to cover a half mile before we reached the shelter of the Broadwater. In these conditions we always sailed with the storm boards in, and although we had wheel steering it could be disconnected quickly and I preferred to use the tiller, then I could wrap one arm around a winch if it was a case of having to hold on. The other three of the crew also knew that they should wrap an arm around a winch and crouch down.

We sailed with the motor going and the mainsail up along the leeward side of the channel which was only about thirty meters wide. This gave us the room to luff into the biggest waves. We were almost clear when a really big wave reared up out of nowhere. It seemed to come at us at nearly spreader height. The boat lifted, and was nearly over the top of the wave, when the crest broke, and the lot came crashing down on top of us. This time I had been a little late in turning in to the sea, and the wave caught us on the port bow.

The old entrance at its worst at low tide. Note, the blind gutters and sand banks.

What a contrast to the current seaway where it’s safe for quite large boats to enter.

The cockpit was full of water which emptied quickly enough, but when we got back onto course again the boat felt strangely sluggish, and it was not until back safely in smooth water and the storm boards were out that we discovered water nearly up to our knees in the cabin. The port side windows had blown in, and some of the pieces were imbedded in the upholstery on the opposite side of the cabin.

Home never looked so good when we tied up at the jetty. Thirty six hours without sleep and a near disaster.

And I DID increase the thickness and strength of the windows in all the boats we built from that time on.

My thanks to the Gold Coast Library Service for the photo of the entrance, and to the Southport Water police for the use of their photos.